Not everyone in the camp could be saved. Not everyone could be helped. In her book “Czy świadek szuka zemsty?” [Does a Witness Seek Vengeance?], Danuta Brzosko-Mędryk, a former prisoner at Majdanek concentration camp, observes that even the most extensive monograph cannot hope to convey the whole brutal truth of the harsh reality that marked the years of Nazi occupation, because to do that, one would need to encompass the life or death of every individual prisoner.

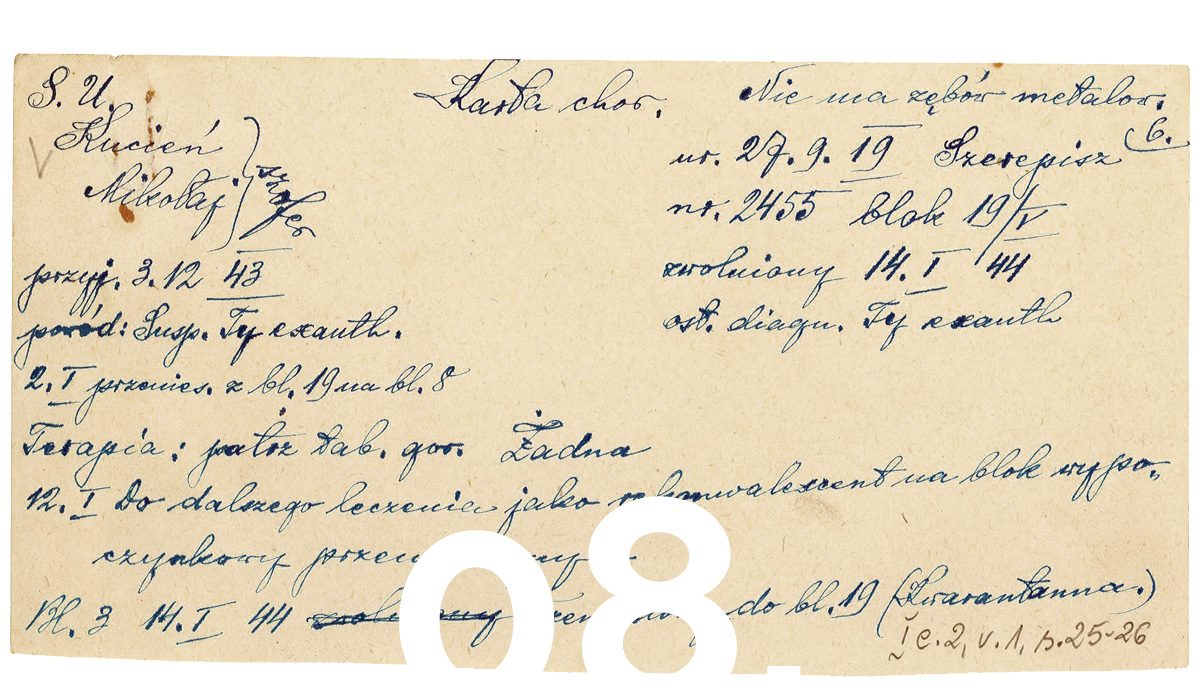

KL Lublin, commonly referred to as Majdanek, was in operation from October 1941 to July 1944. In that period, approximately 150,000 prisoners passed through its grounds, citizens of many countries and representatives of various ethnic and social groups.

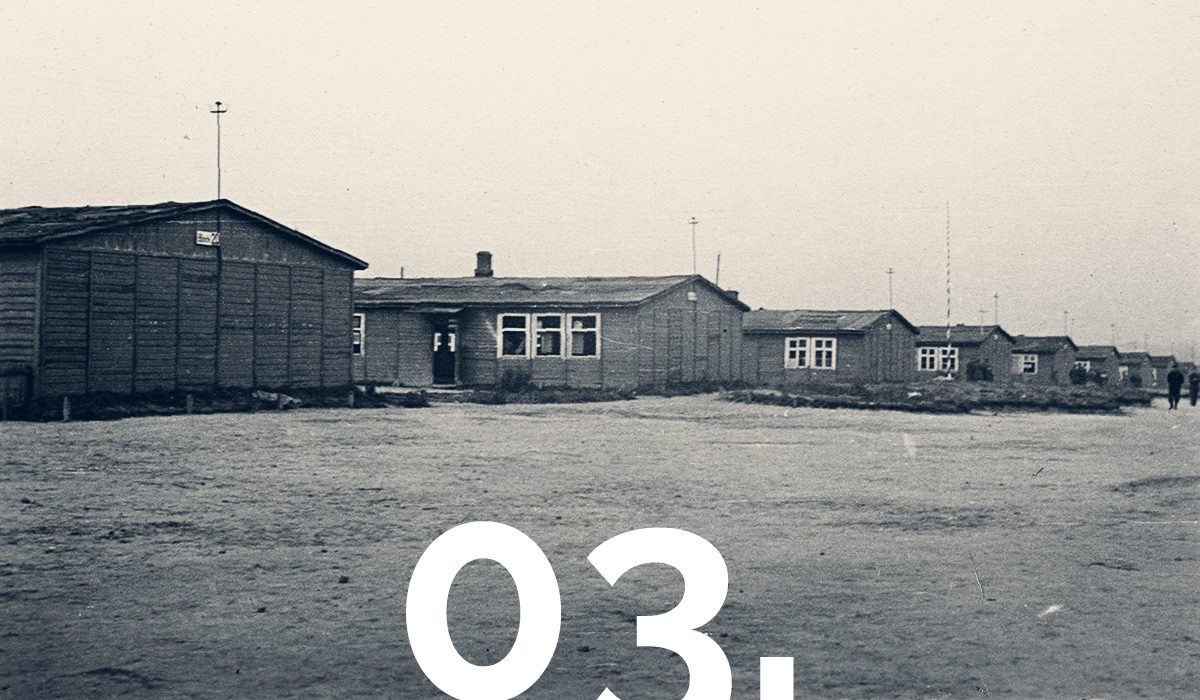

Krankenrevier, literally sick area, was composed of a separate group of barracks where prisoners too sick or too weak to work were quartered. The prisoners referred to it as the infirmary or the camp hospital.

For formal reasons, the establishment of an infirmary was included in the original plans of Majdanek concentration camp, however, in the beginning of its operation prisoners were deprived of any healthcare. The first physicians were brought to Majdanek from KL Sachsenhausen in late November 1941, followed by others from KL Dachau and KL Buchenwald in December 1941 and from KL Auschwitz in February 1942. At the time, their duties were limited to examining prisoners, burying bodies, or work at the clothing warehouse.

The first female prisoners were interned at Majdanek’s prisoner field V. After the arrival of female political prisoner transports from Radom and Warsaw, it was here that the first isolation barrack for women was created. By the end of Majdanek operations, the female infirmary comprised up to even 10 blocks.

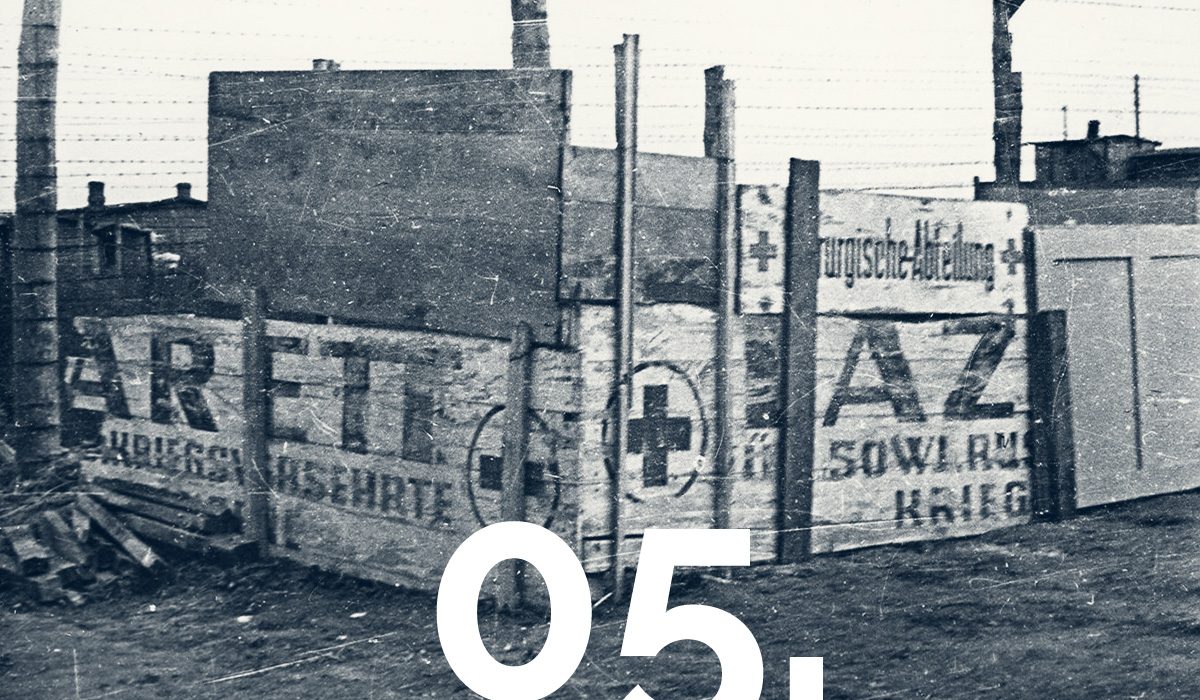

In January 1943, Heinrich Himmler issued the order to establish an autonomous field hospital for Soviet prisoners of war in one of the fields at Majdanek. It was to quarter invalids who had suffered injuries or contracted diseases while fighting in the Red Army, as well as the prisoners who had gone over to the German side.

Czytaj/Read more

Majdanek was considered to be one of the harshest camps. The wooden barracks provided little shelter from the cold and rain. Two small stoves placed in each one were not nearly enough to heat the large and draughty rooms in winter. Similarly, the living conditions of the patients hospitalized at the infirmary was catastrophic. The infirmary barracks were furnished with three-level plank beds, each with a paillasse and a single blanket.

Majdanek prisoners had to suffer constant hunger that led to the development of hunger disease and was, beyond any doubt, an element of the organized system of extermination. The disastrous level of sanitation at the camp favored the spread of communicable diseases such as typhus fever, tuberculosis, malaria, respiratory infections with pleural reactions and idiopathic pneumothorax.

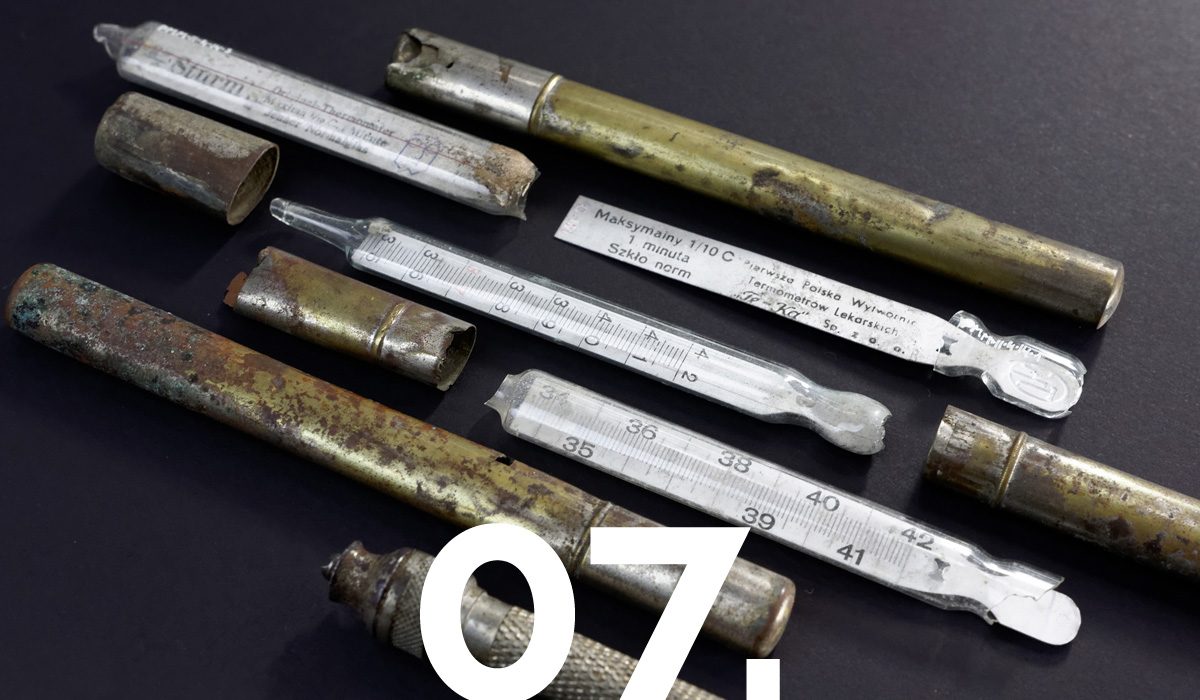

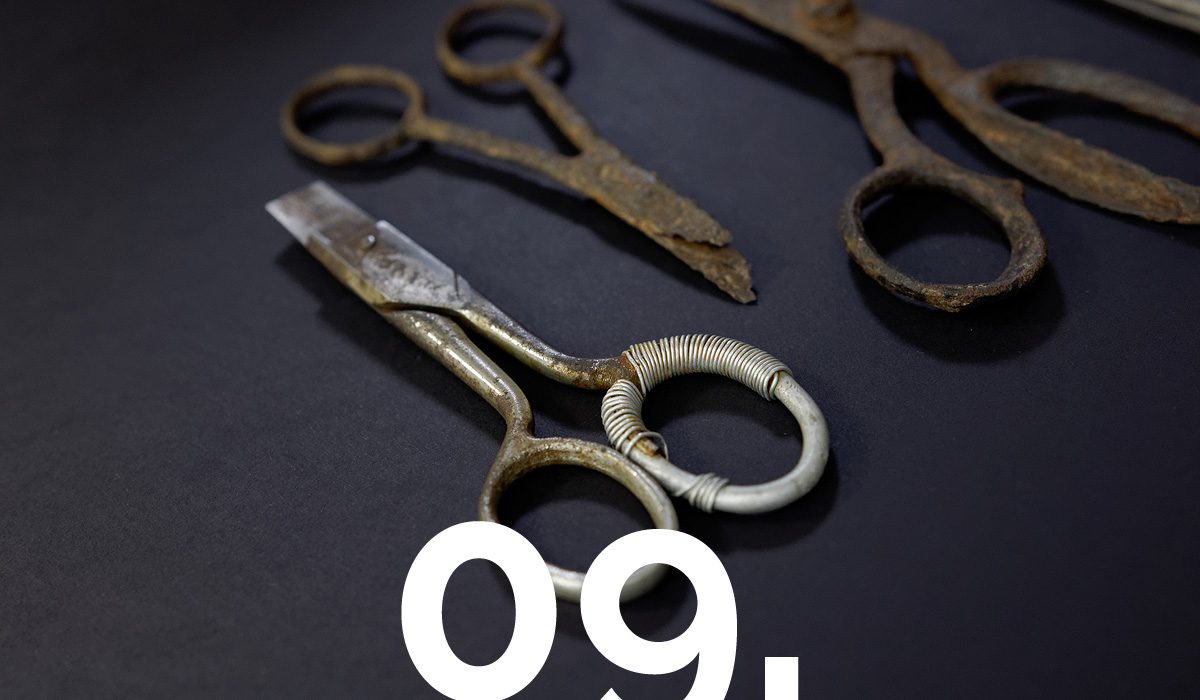

When former prisoners talk of a “pharmacy”, they usually refer to a cabinet in the functionaries’ room, less commonly a separate small room, where the painstakingly gathered medicines, dressings and vaccines were kept. The actual pharmacy could only be used by the SS.

Similarly to other concentration camps, Majdanek saw its share of pseudo-medical experiments conducted on prisoners. The fact was uncovered by doctor Henryk Wieliczański during a scientific session held in Lublin in 1964. The resulting investigation was conducted by the Regional Prosecutor’s Office in Lublin between 1967 and 1973.

In the camp jargon, a “gammel” was a patient in the final stage of physical exhaustion and beyond any hope of recovery. They were placed in special barracks known as gammelblocks. Such barracks were situated in every male field of the camp, separated from the rest of the area with a tall fence. Those confined inside would die in slow agony, deprived of food or any medical attention.

Between mid December 1943 and mid March 1944, Majdanek received so-called transports of infirm and crippled prisoners arriving here on the order from the Reich Main Security Office. These were composed of extremely emaciated and terminally ill patients. Many did not survive the winter journey on a cargo train. Men and women were brought in from the camps in Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Neuengamme, Mauthausen, and Ravensbrück.

Dr Henryk Wieliczański na terenie byłego obozu po wojnie / Dr Henryk Wieliczański on the grounds of the former camp after the war

In total, around 150,000 people of various nationalities passed through the camp at Majdanek, of whom nearly 80,000 lost their lives. Half of those deaths resulted from indirect methods of extermination: primitive living conditions, back-breaking work, disease and epidemics. The highest mortality rate accompanied the typhus fever epidemic in the first phase of the camp’s operation and after the so-called “sick transports” started coming at the turn of 1943 and 1944.