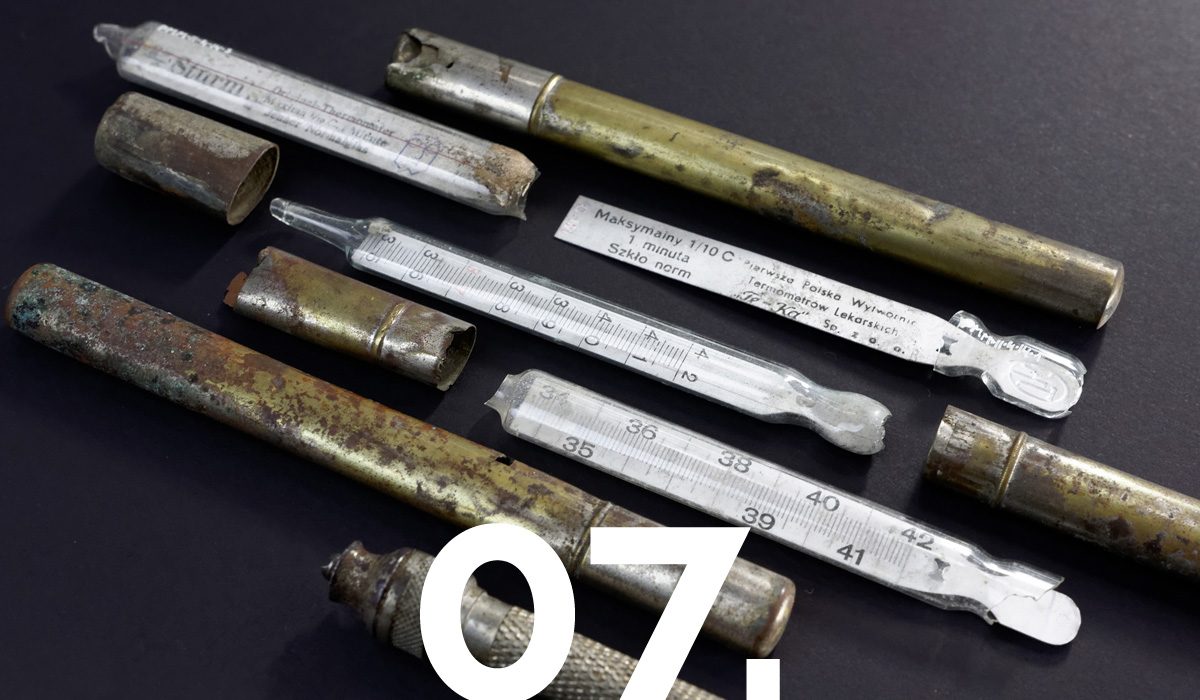

Majdanek prisoners had to suffer constant hunger that led to the development of hunger disease and was, beyond any doubt, an element of the organized system of extermination. The disastrous level of sanitation at the camp favored the spread of communicable diseases such as typhus fever, tuberculosis, malaria, respiratory infections with pleural reactions and idiopathic pneumothorax.

Wounds from beatings and frostbite would often form abscesses or phlegmons. Wounds would generally not heal due to avitaminosis and protein deficiency. The skin of virtually every prisoner was covered with bite marks left by fleas, lice, bedbugs and flies. Scabies would often spread to nearly the entire body of an emaciated prisoner, while secondary infections often led to the formation of skin abscesses, so-called phlegmons. And the collapse of one’s mental strength usually meant the break-down of somatic resistance as well. Those who found themselves alone, unable to rely on support from friends, quickly withered and died at the camp.

A prisoner’s daily food ration contained between 800 and 1000 calories. Malnutrition combined with back-breaking work under extreme conditions resulted in chronic caloric deficiency as well as vitamin and microelement deficiencies leading to the development of hunger disease whose main symptoms include diarrhea and edemas. Skin becomes rough and desquamated. Hair loses color and comes out. Movement becomes astigmatic causing frequent falls. In the second phase, mental, intellectual and emotional response is dulled. Thinking becomes difficult, there are problems with comprehension and memory which are commonly accompanied by apathy and resignation. The delayed reactions to commands and general physical heaviness were treated as “laziness” or a form of protest, and led to punishment and harassment. The final stage of the disease involves a state of complete physical exhaustion and mental break-down, which eventually leads to death.

Diarrhea is not a disease but a symptom of a disease. Diarrheas were widespread and, in my estimation, some 70% of all deaths in the camp were caused by diarrhea. What cauased the diarrheas, what was the nature of the disease? I don’t know to this day. I can only assume based on the extent of diarrhea and the general condition of patients suffering from it, that it was the terminal complication, the outcome of the hunger disease, exhaustion caused by hunger, extreme emaciation – extensive changes in all bodily organs caused by the hunger disease,… the hunger disease affects the entire, let me stress that, entire organism.

— Romuald Sztaba, MD

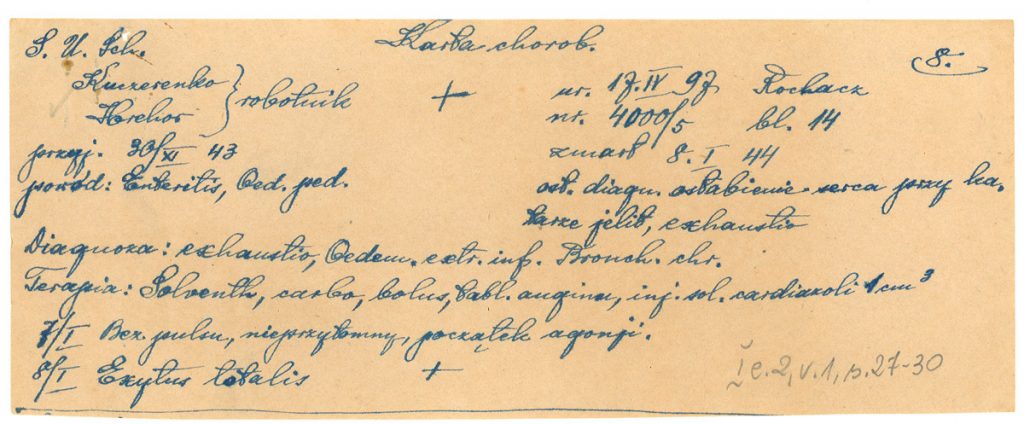

Hospital chart of Hrehor Kuczerenko. Died from exhaustion and diarrhea on January 8, 1944, PMM

Photograph of Ania Rempa, a child of Zamojszczyzna, released from Majdanek in August 1943 through the efforts of the Central Welfare Council. The girl died in hospital soon after, PMM

The first instances of typhus fever were observed in Russian prisoners brought to Majdanek in December 1941. By June 1942, around 2 thousand prisoners had already been infected and the German camp command decided to “solve the problem” by taking a group of sick patients to Krępiec Forest and murdering them there. However, despite the murder of infected prisoners and initiation of pseudo-disinfections which involved transferring prisoners from one field to another, in a system similar to that used at KL Auschwitz, the incidence of typhus did not decrease. In 1943, communicable disease barracks were already also present in male fields: II, III, and IV. The gas chamber located past the male baths, the so-called bunker, was converted into a disinfecting chamber after the extermination of Jews on November 3, 1943. Cyanide gas was used inside to delouse prisoner clothing and SS uniforms. None of these efforts proved fully effective.

(…) the Revierkapo performed a selection of prisoners suffering from typhus fever in entire field I – over 1,500 patients were taken by truck and on horse-drawn carts to Krępiec Forest – I later found out they were murdered and buried in that forest. That is how they fight with typhus fever epidemics at Majdanek. We must no longer diagnose typhus fever at our pseudo-hospital – we are to misdiagnose the disease as pneumonia. The first person to have contracted typhus fever after that “epidemiological action” was the infirmary kapo himself – he now lies in isolation in block I and the entire camp wishes him death.

— Jan Nowak, MD

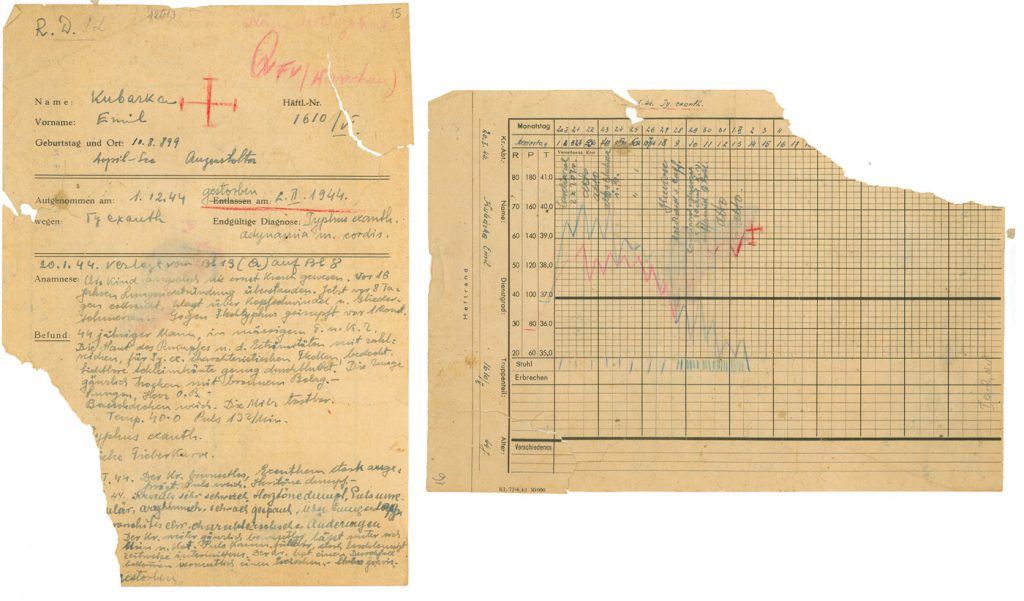

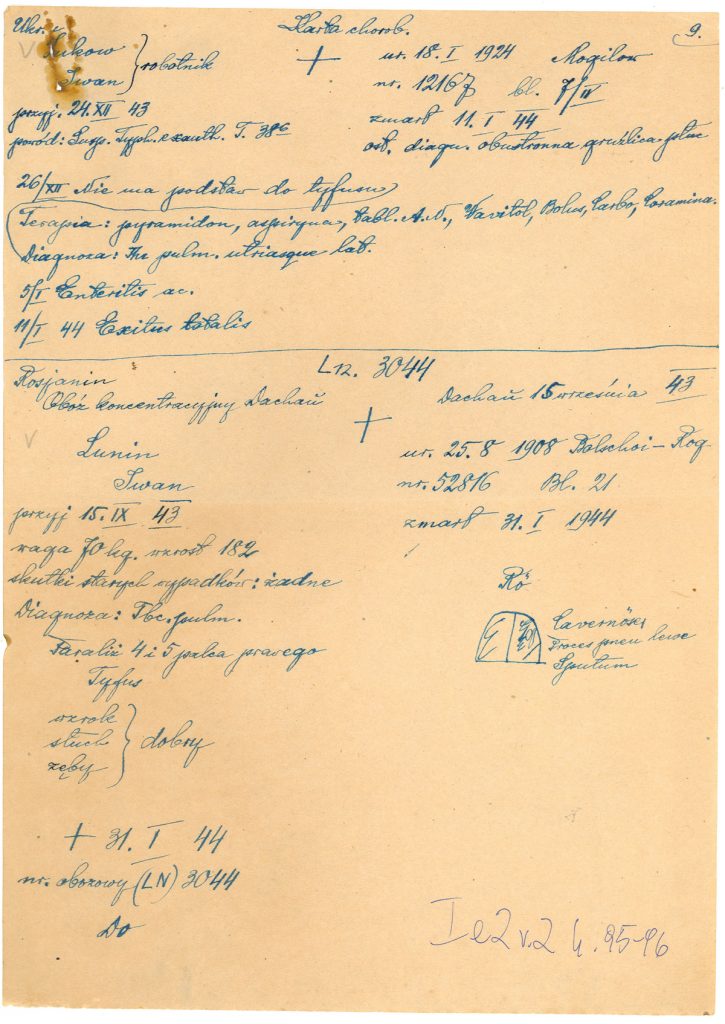

Hospital chart of Emil Kubarka. Died from typhus on February 2, 1944, PMM

Tuberculosis was one of the most common contagious diseases at the camp. Its spread was exacerbated by malnutrition, stress and disastrous sanitation. The TB patients’ condition would typically deteriorate after the camp-wide delousing actions, which were accompanied by baths in a tub placed, regardless of the weather, outside the barrack. Moreover, prisoners had to wait naked in the biting cold, sometimes for hours, to have their clothing returned, which often lead to a general breakdown of their physical condition.

The block housed several hundred TB patients. It was tightly packed with three tier beds, barely heated, dark and dirty. The patients lay in their shakedowns (paillasse and blanket) and spat terribly into some tin cups or jars imitating spittoons, sometimes directly on the floor. The extreme emaciation of these people was astounding (…). The death toll was high, there was virtually not a day without at least a dozen or so corpses being carried out.

— Józef Korcz

Hospital chart of Ivan Lunin. Died from tuberculosis on January 31, 1944, PMM

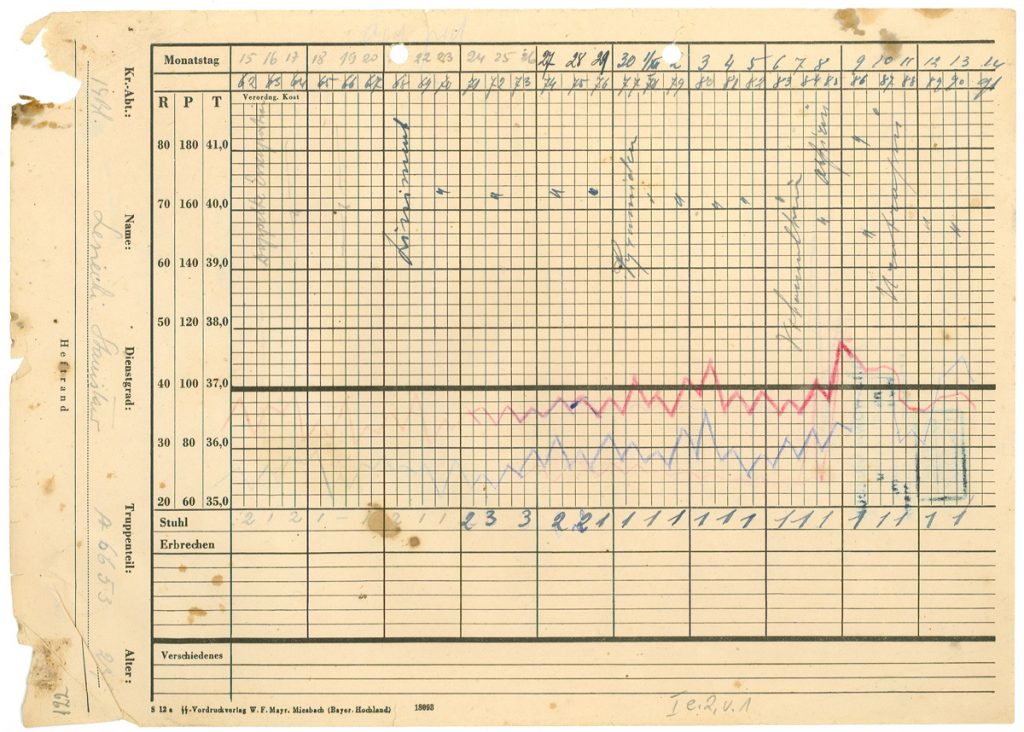

After two or three weeks, I came to work one day so weakened that I was unable to walk. My head hurt, so did all the bones in my body. I had no appetite, only thirst. The only comfortable position was to sit huddled up. (…) The next morning, friends carried me out to the roll-call. By then I was too weak to stand so I lay on the ground. I was perfectly aware that there could be no hope for me, my days were counted, there would be no help. (…) Once the commandos marched out to work after the morning roll call, I somehow crawled my way back to the block. The Stubendinst, a Russian named Sasha with whom I was on good terms, I shared food from my packages, cigarettes, and I always left my package from home with him when I went out to work, when he saw the condition I was in, he said: “You have to go to the infirmary”. He took me to block 11, there was a doctor there. They took my temperature and it was 39.6 °C, they told me to wait for march off to the field V infirmary. It was raining that day. They gave me a blanket to wrap around me and I followed my fellow inmates in a funeral march to the infirmary, 5th block. […] When I think about it today, it all seems like a bad dream. All I remember is a lot of beds and orderlies busy with carrying out the dead.

— Henryk Nieścior

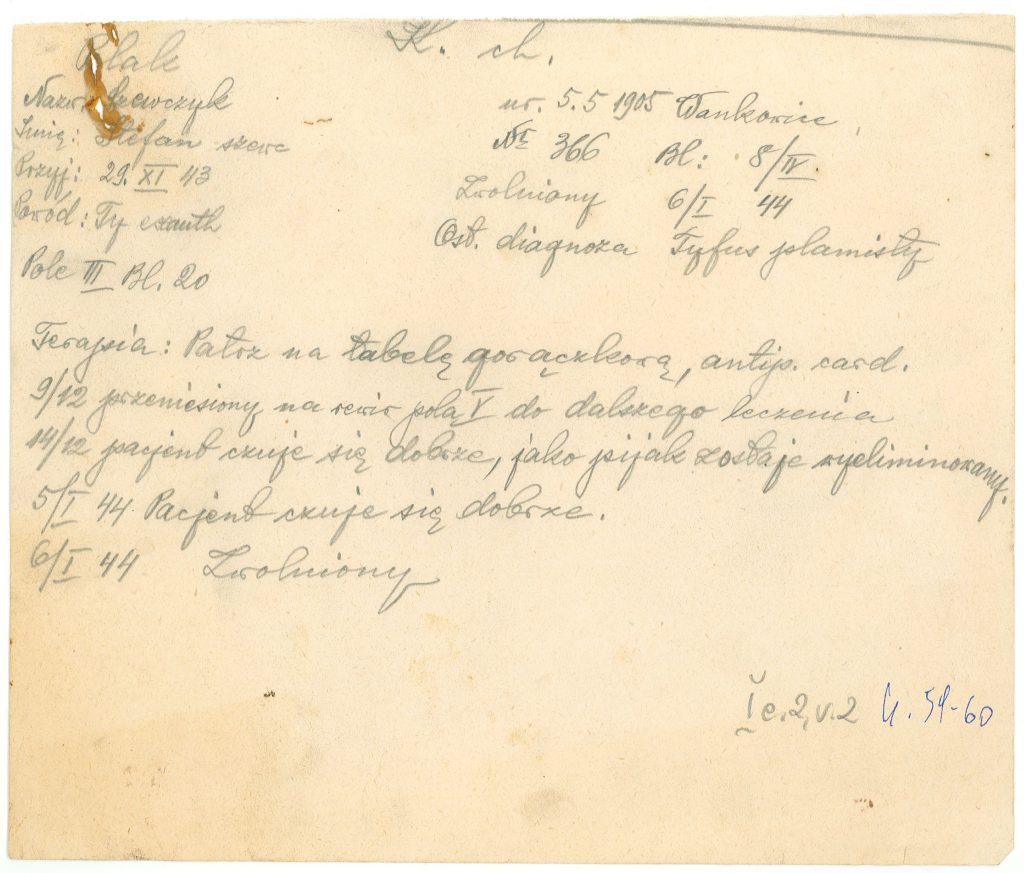

Hospital chart of Stefan Szewczyk, PMM

Hospital chart of Stanisław Lisiecki. Died from hunger sickness on January 9, 1944, PMM

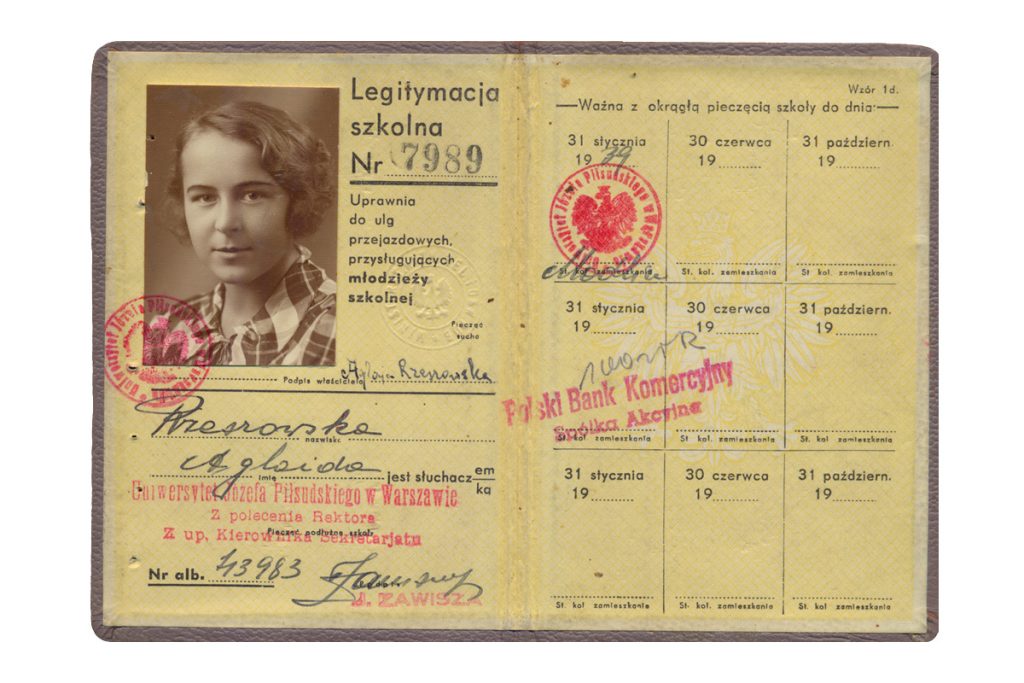

Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko

Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko