In total, around 150,000 people of various nationalities passed through the camp at Majdanek, of whom nearly 80,000 lost their lives. Half of those deaths resulted from indirect methods of extermination: primitive living conditions, back-breaking work, disease and epidemics. The highest mortality rate accompanied the typhus fever epidemic in the first phase of the camp’s operation and after the so-called “sick transports” started coming at the turn of 1943 and 1944.

The infirmary personnel did their best to protect their patients in every way possible. But the impossibility of any meaningful diagnostics or therapy meant that recovery from disease verged on the miraculous.

The Jewish prisoners faced the harshest reality at the camp. They were subject to selections and mass murdered by their captors. Prisoners of Jewish descent were also denied easy access to the infirmaries. Not every Jewish doctor was allowed to work at the camp hospital, and those who did were murdered on November 3, 1943, during the mass executions. This fact is unique for Majdanek as in other camps, being chosen for work at the infirmary provided some protection and a better chance for survival.

I ask: “Is there any chance for me to be chosen for the infirmary, or at least to work as a pfleger [nurse] at the block?” He smiles sadly: “You’d have to be really lucky, Tadzio! They don’t need doctors here. There are some working at the infirmary in field I. They are all very old prisoners. The pflegers [nursing staff] working in the blocks are all friends of the block capos and have nothing to do with medicine, maybe apart from sending people to the next world. I was lucky. A week ago, an Oberkapo broke his arm. I made a makeshift dressing for him. He’s grateful. Promised to talk to someone. Maybe, maybe I can make it.”

— T. Stabholz, MD talking to Leon Tonenberg, MD, a surgeon from Warsaw

I believe that anyone with anything to say about establishing the guilt and limits of responsibility for the crimes of Nazism should speak out. The process in Düsseldorf has two aspects. One is the individual responsibility of the particular defendants and the duty to prove the fact that they committed the crimes with which they are charged. The second aspect far surpasses each individual case. It is about defending certain civilizational accomplishments that Fascism defiled using people such as those very defendants.

— Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko, MD

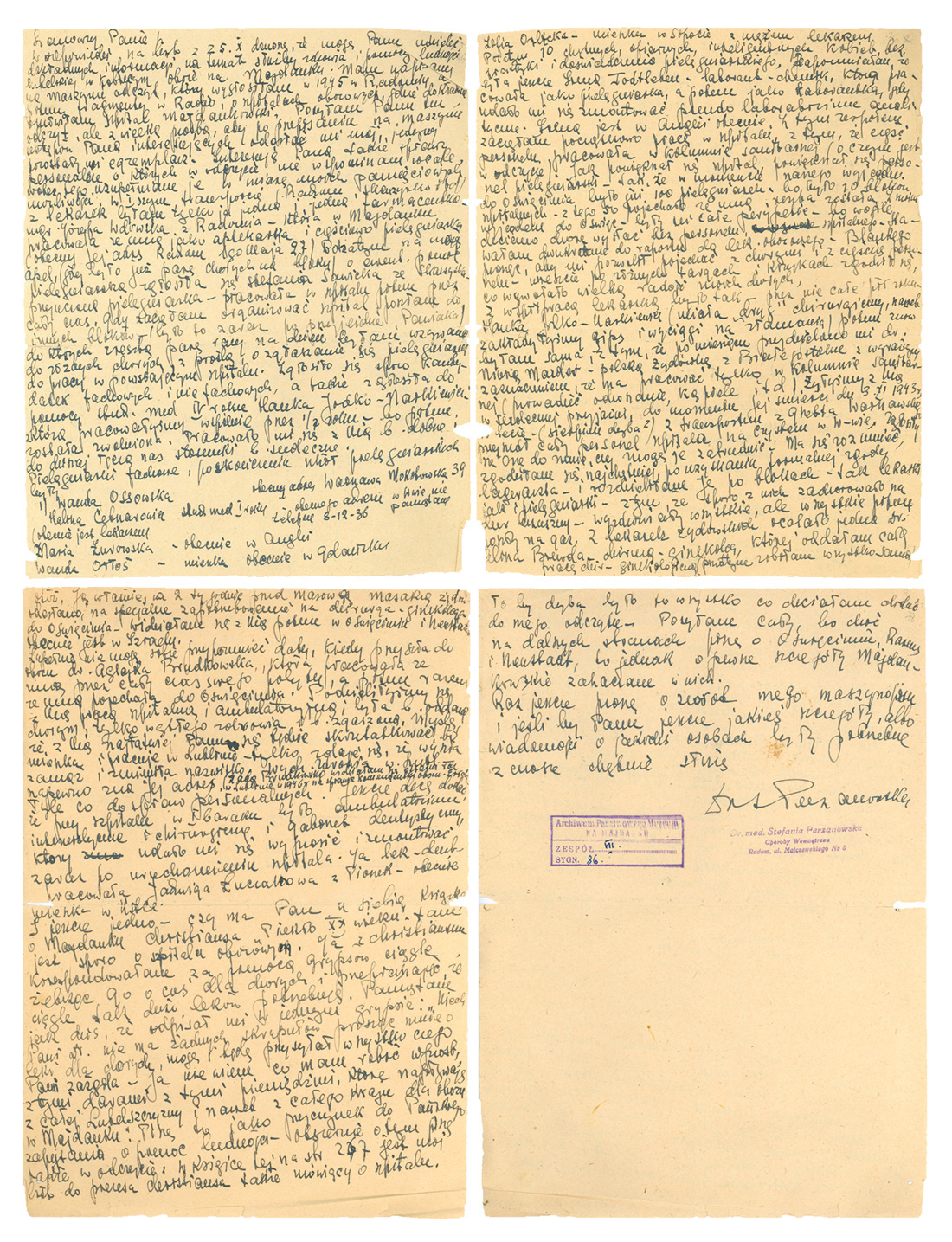

Account of doctor S. Perzanowska about the operation of infirmaries at Majdanek, PMM

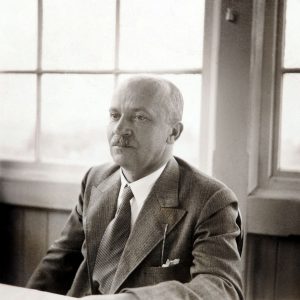

Dr Stefania Perzanowska, picture taken after the war

Romuald Sztaba (first row, second from left) in a group of doctors, 1940

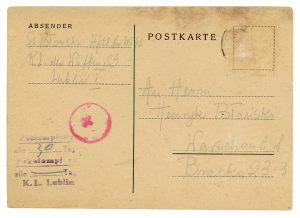

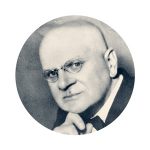

Henryk Wieliczański’s prescription forms, PMM

prof. dr Mieczysław Michałowicz during a medical visit at the Clinic of Pediatrics on Litewska Street, CKPSS

Jan Klonowski (stoi pierwszy z prawej) kilka dni przed aresztowaniem, 1940

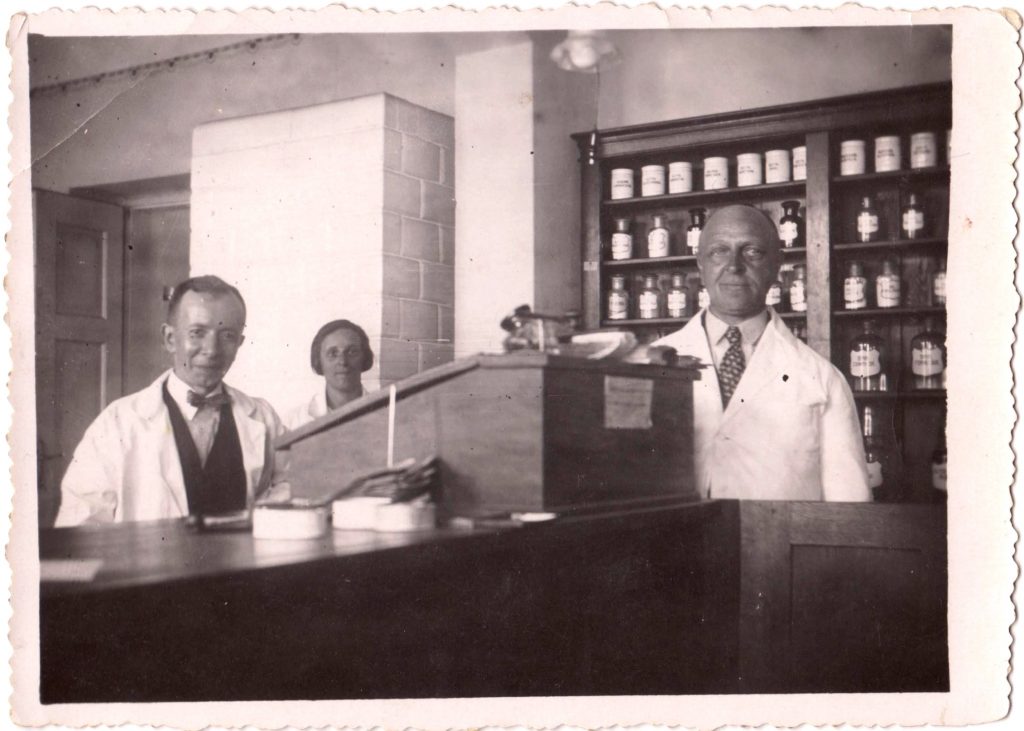

Jan Kayzer (pierwszy z lewej), apteka w Kole, lata przedwojenne

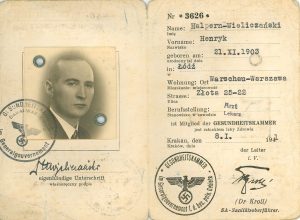

Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko

Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko