Krankenrevier, literally sick area, was composed of a separate group of barracks where prisoners too sick or too weak to work were quartered. The prisoners referred to it as the infirmary or the camp hospital.

Similarly to other concentration camps, the administrative unit responsible for healthcare and sanitation at Majdanek was section V. It was headed by an SS physician assisted by paramedics. In reality, the SS doctors failed to provide even the most basic healthcare to prisoners. The personnel recruited from regular camp staff, often had neither the knowledge nor experience to perform specialist procedures, which commonly resulted in the patient’s death when they tried. The infirmary was also the site of selections conducted by German physicians and SS men during which those suffering from more serious diseases, especially typhus, were singled out and sent to the gas chambers. In certain reported cases patients were also murdered by intracardiac injections of phenol or Evipan. For those reasons, some prisoners referred to the Infirmary as the “vestibule of gas chambers” and refused to come in regardless of how serious their condition was.

The typical German doctor was a middle-aged man with a stout torso supported by skinny legs, wearing shined calf-length, leather boots and a monocle or pince-nez rested on a turned-up nose, and shaded by the visor of his officer’s cap. They invariably exuded dominance and contempt as they drawled out their words, usually carrying a whip and accompanied by a leashed dog. Those callous pen-pushers inspired barely contained hatred and indignation in us. I have never heard them discuss anything related to medicine. I have never seen them practice any actual medicine. The [SS] doctors seemed more like hound dogs ready to leap at their pray at any time. There may have been exceptions but not to my experience.

— Suren Konstantynowicz Barutczew, MD

The direct healthcare was provided to patients by prisoner-physicians of various nationalities with the support of orderlies, paramedics, nurses and translators.

The infirmaries were organized in wooden barracks that initially lacked even the most basic facilities such as a sewage system. Not only the necessary equipment but even actual medicines or medical instruments were in desperately short supply. Neither actual diagnostics nor any form of meaningful treatment was possible. In time, the conditions began to improve somewhat. Medicines and instruments were obtained by the prisoner-physicians and pharmacists themselves with the aid of the Polish Red Cross, the Central Welfare Council, families of the prisoners, and private donors from Lublin.

The infirmary is overcrowded with patients. The death rate increases exponentially. Typhoid and dysentery, commonly referred to as Durchfall, run rampant. This is now further exacerbated by the heat and shortage of water. The epidemics spread every day and there are no medicines or disinfectants available. As concluded by our SS-woman “supervisor”, no-one and nothing can prevent the spread of disease, the hunger and the lack of basic sanitation. The crematorium cannot keep up with incinerating all the bodies.

— Eugenia Deskur-Dunin-Marcinkiewicz

Objects found at the former camp grounds, PMM

Objects found at the former camp grounds, PMM

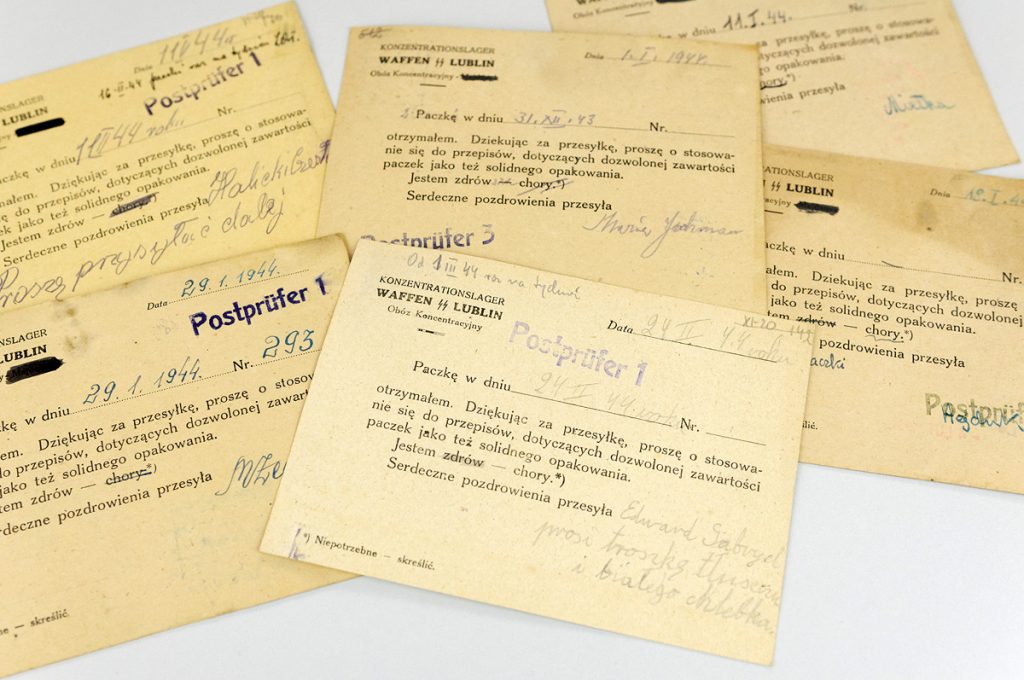

Red Cross cards on which prisoners thanked for the received packages and reported their physical condition, PMM

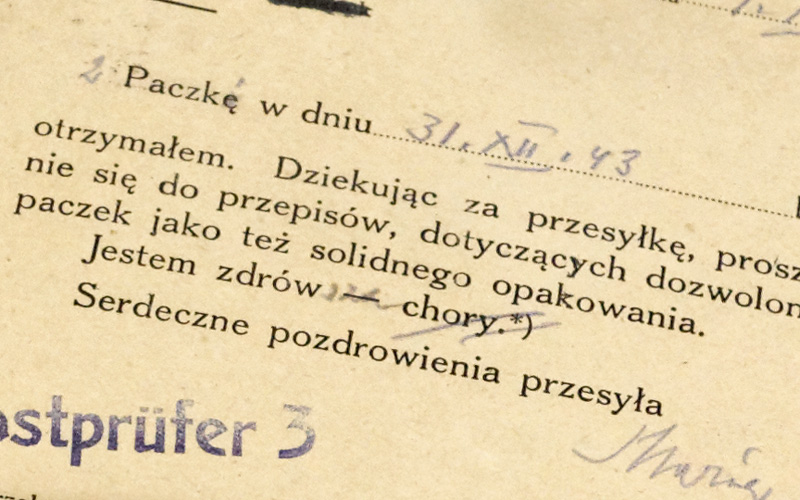

“I am healthy (healthier)” – a handwritten annotation on a card of the Red Cross, PMM

The SS doctors

Blancke Max, MD

Bodmann Franz, MD

Fischer Karl Josef, MD

Helmersen Erwin, MD

Kaiser Alfred, MD (an SS dentist)

Popiersch Max, MD

Rindfleisch Heinrich, MD

Rittinghaus Helmut, MD (the SS pharmacy)

Schmidt Heinrich, MD

Schütz Karl, MD (an SS dentist)

Trzebinski Alfred, MD

The SS orderlies

Enders Anton

Haberlacht Bernard

Hansen [Hanson] Herbert

Havenith Bernard

Konietzny Günther

Perschon Hans

Reinartz Wilii